Pentecost

Nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them.

The opening eleven chapters of the book of Genesis seek to explain why the world is the way it is. And though these stories were first told thousands of years ago, they offer a surprisingly accurate vision of our world, even today.

The final story of this opening section of our Scriptures is none other than the Tower of Babel. A capstone story told in a single paragraph.

Genesis tells us that the whole earth had one language, and few words. Though they did not say much, like today, mass communication was easy.

But what they did choose to say to one another speaks volumes. Only twice in this passage are the words of this ancient civilization recorded, and yet both times the same phrase is used by those building the Tower:

Let us make bricks, and burn them thoroughly.

And they had brick for stone. Then they said,

Let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens,

and let us make a name for ourselves.

Let us make is not neutral language in the narrative of Scripture.

It is God himself who first says Let us make in Genesis 1 when he creates the first humans in his image.

And in Genesis 11 we see humanity taking the creative reins.

It begins innocently enough: let us make bricks. The mandate given to humanity to subdue the earth has begun to play out. Humanity is learning to master the natural world through the use of technology.

Technology helps us accomplish our goals faster, more efficiently, and without getting our hands quite as dirty.

If your goal is to wear clean clothes to work each day, a washing machine and dryer will go a long way in helping you reach that goal.

If your goal is to live in Richardson but work in downtown Dallas, a highway system and motor vehicles will go a long way in helping you reach that goal.

But what happens when your goal is less than noble?

What does progress, advancement, and technology offer you if your goal is to gain power? Or punish those you don’t like? Or eliminate entire people groups from the face of the earth?

Technology offers you an opportunity to accomplish your goals faster, more efficiently, and without getting your hands quite as dirty.

Technology does not offer its own moral compass. It simply helps you do whatever it is you already want to do.

And sometimes, it can be scary what our hearts want to do.

Let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens,

and let us make a name for ourselves.

The story of the Tower of Babel is the story of humanity seeking to be the master of their own fate, the shapers of their own world, the judge and jury of what is right and wrong.

They set their minds to establishing a civilization that had no need of God. That’s why their tower broke the plane of heaven.

And it worked.

Genesis tells us that God saw the tower. And his response may surprise you. He did not laugh at their futile attempt. He did not rain down fire and brimstone in righteous anger.

He saw the tower for what it was: an ominous sign of what humanity is capable of accomplishing when left to its own devices.

And the Lord said, “…this is only the beginning of what they will do; and nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them.”

This shiny new tower—built by those who held power out of a desire to reshape the world into whatever they saw fit—was just the beginning.

So God confused their language, and scattered them across the world.

This story stands on its own as a compelling explanation for countless atrocities throughout history and today. Of what happens when an Empire sets their heart on ruling the whole world, when a people set love of country as the highest good, no matter the cost to others, when a leader’s ambition for power blinds them to the trail of destruction they leave in their wake.

The Tower of Babel is a prototype of the story of human history.

But it is not the end of the story.

The Tower of Babel explains why the world is the way it is.

The Day of Pentecost explains the world as it will be.

Against the backdrop of the Tower of Babel, the Day of Pentecost presents a stark contrast.

Instead of mankind charting their own course, the Day of Pentecost begins with God’s people awaiting his direction. Huddled together in a room, seeking His wisdom. Creatures relying wholly upon their Creator.

At Pentecost, Humanity did not reach up to God, attempting to grasp him in their hands. Rather, God came down. It was not human ingenuity that saved the day, but the very breath of God.

The Holy Spirit came to rest on God’s people. And then God’s people got to work.

And the results were extraordinary.

At Babel, confusion reigned supreme. One language became many, and communication became impossible.

At Pentecost, many languages did not quite become one—each maintained its distinct contribution to human culture—but despite these many languages, all barriers to hearing the good news of God in Christ were removed.

What happened next was no less miraculous.

Peter, who weeks earlier denied that he ever knew Jesus, preaches among the greatest (and shortest) sermons you have ever heard, and thousands join the Christian Church.

And it didn’t stop there.

If you can carve out a few hours over the course of this next week, read the Book of Acts.

You will be encouraged, surprised, and maybe even a bit confused. But one thing will ring true as you read: despite many obstacles, conflicts, twists, turns, and dead ends, God was at work in the world in a powerful way through his Church.

God was establishing a new way forward for humanity.

God’s people were given the Holy Spirit, not just to comfort them in Jesus’ absence, but also to teach them to have right judgment in all things. Through the grace of the Holy Spirit, God’s goals can become our goals.

When God saw the Tower of Babel and all that it represented, he knew something had to happen.

This is only the beginning of what they will do;

But now that God’s Spirit lives within his faithful people, the same can be said of the Church.

and nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them.”

The rise of the Christian faith was improbable, to say the least. As sociologist Rodney Stark once framed the question:

How did a tiny and obscure messianic movement from the edge of the Roman Empire dislodge classical paganism and become the dominant faith of Western civilization?

The Christian Church grew from 1000 members in the year 40—.0017% of the population of the Roman Empire—to over 33 million by the year 350. That represents over 56% of the population of the Roman Empire at the time.

But it was not just the impressive numerical growth that points to the power of God at work through the Christian Church to accomplish the impossible.

Deeply rooted practices of the Roman world were challenged head-on by the growing Christian community. The widespread and legal trade of young girls and boys for sex, the killing of unwanted infants, the dehumanizing of slaves, and the worship of the Emperor are just a handful of cultural norms against which Christianity demanded a different path.

These earliest Christians were not seeking ways to be counter-cultural. They were not interested in leading revolutions. They were simply living a life in submission to the God who made them, regardless of how backwards, how different they seemed to the world around them. And as a result of their faithfulness, many of these institutions and practices began to crumble.

The world has its own agenda. Its own temptation to view this life as ours to do with as we please. There are countless opportunities to build towers to make a name for ourselves. And with the help of technology, we might just succeed.

But God has sent his Spirit into the hearts of his people. And when God teaches his people to have right judgement in all things, to direct and rule them according to His will, their very lives will challenge some of the towers being built around them.

And all of this begins, for us, in our Baptism. If you have been Baptized, let the Feast of Pentecost renew in you a commitment to living in the power of the Holy Spirit. If you have not, the invitation stands for you just as it stood for those who were there on the Day of Pentecost.

God is at work in the world, and through the power of the Holy Spirit, you are invited to join Him.

This is only the beginning of what they will do; and nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them.

In the Judaean desert, on an unexpected trip of a lifetime a week before our 15 year anniversary.

Church of the Annunciation, Nazareth.

Moral idiots and a liberal arts education

The paragraph below, from Alan Jacobs, is an important one to comprehend. The rest of his post helps frame some of the wider issues at hand, and points to other helpful works for those seeking to read more widely on these things.

I want to make a stronger argument: that the distinctive “occupational psychosis” of Silicon Valley is sociopathy – the kind of sociopathy embedded in the Oppenheimer Principle. The people in charge at Google and Meta and (outside Silicon Valley) Microsoft, and at the less well-known companies that are being used by the mega-companies, have been deformed by their profession in ways that prevent them from perceiving, acknowledging, and acting responsibly in relation to the consequences of their research. They have a trained incapacity to think morally. They are by virtue of their narrowly technical education and the strong incentives of their profession moral idiots.

While it is not the only point of the paragraph, I cannot help but revisit the final sentence (emphasis mine):

they are by virtue of their narrowly technical education … moral idiots.

Learning to lead, love, and serve our world does not require more technical training, either in K-12 or higher ed. It requires more humane teaching and learning.

Your eight year old can learn to code from an app whenever they need it, whether that is this summer or twenty summers from now. They cannot so easily learn what it means to be a human being who is a member of a human society, while also learning to master the art of letters and numbers.

One of the best things you can do now to prepare young children for the moral idiocracy of our age is to ground them in a rich education in the liberal arts.

The World, the Flesh, and the Devil. These are the three forces that aim to tear down the creatures of God. And in the Good Shepherd discourse, Jesus sets himself against the final of these forces: evil itself..

What an exciting turn of events it would be to see Wrexham promoted to League Two and Chelsea relegated to the Championship in the same season.

Not entirely likely, but certainly possible.

Being part of a Diocesan email listserv and serving as a parish priest both mean that I regularly read announcements of death. This also means that I regularly read about death in theologically rich language.

Our sister in Christ was born into the greater life. May she rest in peace, and rise in glory. Light perpetual shine upon her.

Letter to Students: On ChatGPT, for now

You happen to be a student at a fascinating moment in the history of information and technology. It is not unlike being a student in the years when the search engine, or the personal computer, or even the printing press were first popularized.

ChatGPT, and other instances of AI, offer a new way of interacting with information. Decades ago the search engine revolutionized research by giving all of us access to a seemingly endless number of sources. If we have a question about how to replace a radiator in our car, a search engine can point us to thousands of videos and websites that each claim to give us the right answer.

ChatGPT, on the other hand, will take information from those very sources and formulate an actual answer to your question.

Search engines can point you sources where you can find answers to your question; ChatGPT can answer your question itself. Or at least try to. Just as search engines cannot guarantee that the websites, videos, and documents they point you towards are actually good and true, and ChatGPT similarly cannot promise that the answers it gives to your questions are good and true, or even factual.

In our academic context, these AI tools can be used in at least three ways.

As a form of blatant plagiarism

As a shortcut for the hard work of critical thinking

As a potentially helpful tool for initial research

My recommendation in the short-term is this: for now, don’t use it at all for your academic work.

Way One: Blatant Plagiarism

The first way you can use it—as a form of blatant plagiarism—is not only easier to detect than you think, but a serious breach of your own academic integrity. Representing an AI bot’s answer as your own—even if you modified that answer significantly—is a clear form of academic dishonesty. You know this already, but I think it is worth sharing at this point.

Way Two: As a shortcut for the hard work of critical thinking

The second way to use it—as a shortcut—seems better than the first on the surface, but it actually has long-term affects that are just as bad, if not worse.

When new technologies emerge, it often takes some time for a society to recognized the unintended consequences of that new technology. Nuclear technology emerged relatively rapidly in the twentieth century. And it has led to the rise of both nuclear weapons and microwavable bacon. Put mildly, both are detrimental to human flourishing.

This is where we are with ChatGPT: we are impressed that it can do some things well, but we are not quite sure what the long term unintended consequences will be.

What will society look like a generation from now if most of today’s students shortcut the process of learning to think slowly and critically about things that matter most?

What will a church, or city, or family look like if it is made up of a large percentage of people with underdeveloped intellectual muscles, who lack the strength to think wisely on their own, and instead outsource their thinking to an algorithm? (One that, even according to its creators, does not actually think, but rather pieces together what others have thought.)

Using AI as a shortcut to critical thinking is wrong because it falls short of academic honesty, but it is especially wrong because in taking the shortcut you are missing out on developing a mental muscle that your friends, your parents, and your future spouses, children, fellow Christians, and co-workers all need you to have.

Way Three: As a potentially helpful tool for initial research

I do think there could be a way for this new technology to be used properly as a tool that helps you think more deeply about important academic questions you are facing. I have a hunch that when used as a research tool to discover excellent sources—not to answer important questions themselves—it may have something to offer students today and in the future.

But I don’t yet know how to pull this off myself, and therefore I am highly skeptical about your own ability to do so at this point.

We will have more to share about these things with you, your parents, and our wider school community as we prepare for next school year.

There is a lot you can do with ChatGPT and tools like it.

You can blatantly plagiarize, and get caught.

You can blatantly plagiarize, and not get caught.

You can use it as a shortcut to deep, critical thinking and get caught.

You can use it as a shortcut to deep, critical thinking and not get caught.

And in each of the scenarios above, you are doing yourself, your community, and your future self and future community a deep disservice.

So again, let me echo my recommendation in the short-term: leave it unused, for now, in all of your academic work.

Soccer is an icon of virtue ethics, and as such it is a form of leisure that points us to what it means to be a moral creature.

Remarks: An introduction to our Rhetoric Capstone Student Presentations

I am encouraged by many things this evening, but I would like to name two of them.

First, I am encouraged to know that this is a place where students are trained to think deeply, slowly, and theologically about things that matter a great deal.

Juniors, your presence here this evening and your work this year is a testament to the many ways you are growing in wisdom and virtue. Well done.

Second, I am grateful that this is a place where adults take time out of their busy weeks to hear students share some of what they have learned this year.

Parents, teachers, and friends of our school: your presence here this evening is a testament to your desire to contribute to a more wise and virtuous Christian witness in the public square.

Our students have selected challenging topics to explore this year, and their teacher has demanded that they read, think, and write wisely about them.

All while many of their peers are being trained to think by social media companies, politicians who want to be celebrities, and celebrities who are famous for being famous.

Though you may—in some cases—find yourself arriving at different conclusions than our presenters, I trust that you will appreciate, honor, and be encouraged by the way our students have thought through these things.

If It Be Your Will by Leonard Cohen is sung from the perspective of Jesus from his arrest and trial through the harrowing of hell, right?

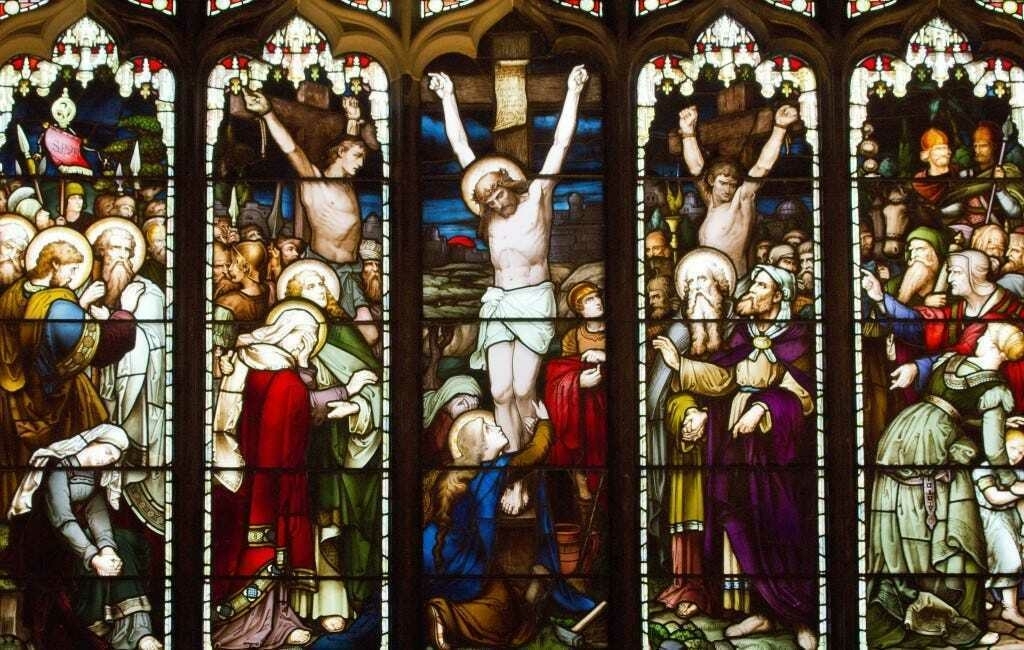

Good Friday

All this he did for you.

In a cold, dark, room somewhere abroad a small group of naked, tired, hungry, and defeated captives are huddled in the corner.

They’ve lost count of the hours, days, weeks, and years since they've experienced anything close to a normal life.

One night, in the middle of a monsoon, an explosion sends a wooden door, now shattered to pieces, across the room. Light floods the room in the form of half a dozen headlamps. Over the ringing of damaged eardrums, the captives hear shouted commands and see choreographed responses. In the blink of an eye, a row of uniformed men approach the huddled captives, shouting something familiar, but forgotten.

The soldiers are shouting, but the captives don’t budge.

“We’re here to save you,” the soldiers scream in as many languages as they can muster.

Still no response.

Maybe it was the shell-shock. Maybe it was miscommunication.

Or maybe, as another prisoner of war once recounted, these captives have been tricked before. Others have come, claiming to rescue them. Most of them have been defeated. Some of them were nefarious; disguising themselves as Navy Seals before beating their captives senseless for attempting to leave with the enemy.

Time is running out, but the captives have been down this road before, fooled by a would-be savior, and this time, they don't budge.

It may surprise you to hear this, but Jesus of Nazareth was one of dozens of young Jewish teachers to be put to death by the Romans in and around first-century Palestine.

When Jesus of Nazareth’s followers fled the scene and locked themselves in a room following his arrest, they did so because they, too, had been down this road before.

Ingrained in their collected memories were visions of other would-be saviors who amassed a significant following before getting cross with religious and political authorities. Each messiah figure’s life ended the same way: execution at the hands of the Romans, and arrest or worse for his followers.

In the world of the first century, a crucified Messiah is a failed Messiah. And on that Friday afternoon, the disciples began to realize that the past three years of their lives had been spent following a failed Messiah, one who stands in a long line of other failed Messiahs.

When Jesus of Nazareth’s followers fled the scene and locked themselves in a room following his arrest, they did so because they, too, had been down this road before.

And yet here we find ourselves, two-thousand years later.

A Jewish messianic figure publicly executed by the Roman government would not make the back page of a first-century newspaper; how in the world did we wind up here?

The cross has become one of the most universally-recognized symbols on the planet, and Jesus one of the most universally-recognized names.

Why? What made the crucifixion of this Jewish prophet so different from the crucifixion of the others?

On that Friday, the Romans did not nail a revolutionary leader to the cross.

On that Friday, the Romans did not nail a teacher born centuries before his time to the cross.

On that Friday, the Romans did not nail a traveling wise man and miracle worker to the cross.

No.

On that Friday, as one Roman soldier realized moments too late, the Romans nailed God to the cross.

And when God is nailed to a cross, we must respond.

We could respond with detached pity, feeling sorry for Jesus but not knowing what to do about it.

We could respond with debilitating guilt, like Javert who could not even begin to grasp the grace shown to him by Jean Valjean.

We could respond with noise, drowning out the uncomfortable reality of the cross.

Or we could respond with silence.

Good Friday services end in silence, and many Christians spend part of Holy Saturday in some form of silence, too. Not just to remember the silence of the grave, but to reflect on the meaning of the Cross itself.

--

Back in our cold, dark, room somewhere abroad, with our small group of naked, tired, hungry, and defeated captives huddled in a corner, the soldiers cannot believe the captives aren’t moving.

The stalemate continues for what feels like hours, until one of the soldiers stops screaming. He lowers his gun, takes off his own clothes, and crouches down in the corner of the room next to one of the captives.

His fellow soldiers are stunned. The captives hardly notice.

Eventually, one of the captives opens her eyes, and sees what the soldier has done.

One by one, some faster than others, the captives stand and walk towards their rescuers.

Words matter, but not as much as actions.

Do you want to know what God is like?

Do you want to know what God thinks about you?

Do you want to know whether God has love for you, despite what you alone know about yourself?

Look to the Cross.

For you Jesus Christ came into the world:

for you he lived and showed God's love;

for you he suffered the darkness of Calvary

and cried at the last, 'It is accomplished';

for you he triumphed over death

and rose in newness of life;

for you he ascended to reign at God's right hand.

All this he did for you, child, though you do not know it yet.

And so the word of Scripture is fulfilled: "We love because God loved us first.”

Maundy Thursday

Learning from Jesus “on the night in which he was betrayed.”

In first-century Galatia, a small but powerful group of teachers insisted that anyone who wanted to become a Christian must show that they are truly Christian through some outward sign. A very specific outward sign, in fact: circumcision.

After dismantling this argument throughout his letter to the Galatians, St. Paul proposes his own outward sign of the Christian faith. In what has since been dubbed the “Fruit of the Spirit,” he lists several outward signs (fruit) of a life indwelled by the Spirit.

According to this list, what is the very first thing you should outwardly notice in the life of a Christian?

Love.

Maundy Thursday is a celebration of two sacred moments in the life of Jesus, both of which are wrapped in love. The name itself comes from the Latin work for command (mandatum), since Jesus gives his disciples a new commandment on this sacred Thursday:

A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another: just as I have loved you, you also are to love one another.

This new commandment is shared in two ways, both of which are celebrated each year on Maundy Thursday.

First, Jesus washes the feet of his disciples. Jesus taught that the Son of Man came not to be served, but to serve. And then he followed through by assuming the role of a household slave. Peter’s initial refusal to have his feet washed, followed by his request for Jesus to wash his entire body has always struck me as capturing my own posture towards Jesus: an oscillation between full embrace and keeping what I deem to be an appropriate distance.

After washing their feet, Jesus shares a meal with his disciples. Maundy Thursday is about foot washing, but it is also a celebration of the institution of this sacred family meal.

New Testament scholar N.T. Wright points out something about that evening that is worth considering:

When Jesus himself wanted to explain to his disciples what his forthcoming death was all about, he didn’t give them a theory, he gave them a meal.

Jesus is instituting a very specific meal in the Last Supper, one that has been celebrated every single day somewhere on the planet since the earliest days of the Christian Church. But what is true of the Lord’s Supper can also be somewhat true of each of our meals by extension. I love the prayer below, taken from Every Moment Holy, about all meals and what they can become for us:

Meet us in the making of this meal, O Lord, and make of it something more than a mere nourishment for the body.

What is true of all meals is most true of the Eucharist.

But that Thursday, and this Thursday, are about more than just a meal. When the Last Supper is revisited in 1 Corinthians, Paul reminds his readers that all of this took place “on the night in which he was betrayed.” The cross was on the horizon even as bread and wine were being shared amongst friends on the first Maundy Thursday.

The Last Supper was the beginning of the three most important days in the history of the universe, and so Maundy Thursday is the beginning of the three most important days in our Church Year.

May God use these days to equip us to live out the new commandment he first gave two thousand Thursdays ago.

Because of our sophisticated watches and our ability to schedule our days down to the minute with the push of a button, it is easy for us to misunderstand what time is and how it actually works.

Not all weeks are created equal. And this is no ordinary week.

Holy Week

This is no ordinary week.

A quick note before this edition of the newsletter: Holy Week culminates in a final service on Saturday Evening: The Easter Vigil. If you happen to be in the Dallas area this Easter, come see us at Church of the Incarnation for what I find to be the most moving of all services of the Christian Year. I will be teaching a History & Traditions class at 7pm ahead of the service, which begins at 8pm. Let me know if you plan to attend; seats fill quickly.

Because of our sophisticated watches and our ability to schedule our days down to the minute with the push of a button, it is easy for us to misunderstand what time is and how it actually works.

We tend to think of time as being evenly distributed. There are 24 hours in a day—in every day. So it seems right that any given hour or day or week must be the same length as any other hour, day, or week. More often than not it appears to us that all days are created equal.

Not only is this technically not the case universally-speaking, it is certainly not true experientially.

Some minutes last 60 seconds. Others last what feels likea lifetime.

Time can fly, or it can stand completely still.

Some things in our world take a long time to change. But your world can change in a fraction of a second.

Not all weeks are created equal.

And this is no ordinary week.

Just over two thousand years ago there was a single seven day period of time that has proved to be the most important week in the history—and even in the future—of the universe.

And this is the week where we take that week from the past, and drop it into the present.

Holy Week is the week of all weeks.

This week contains within it all that you and I should expect to experience as Christians.

It has its false hopes. Moments, like Palm Sunday, where it seems that all has been made well, until lofty expectations give way to reality.

This week has the loneliness of Gethsemane, the betrayal of a loved one, the abandonment of friends.

But Holy Week also has its Mondays. The mundane.

Holy Week begins today, but you might not fully notice it until Thursday night. We have a relatively normal Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday ahead of us.

The mundane. False hopes. Betrayal. Loneliness.

Holy Week contains all of this.

This week, if you allow it, will take you even to the depths of sorrow as the Son of God is nailed to a cross.

But only so that you can experience the highest of joys: the defeat of death and the hope of the resurrection.

This is no ordinary week.

But here is the catch: It can be, if you want it to.

You can go about your business, maintain your standing calendar. Tomorrow can be, for you, just another Monday.

Or you can embrace this Holiest of weeks.

If you do, you can expect to experience a few things.

First, you will think things that you normally don’t think.

It is not every week that you wonder what it means for the author of life to die.

Or what your private sin has to do with the Creator of all things.

Or what really happens when all of this comes to an end.

This is a week to think about things you normally don’t think about.

But you will also feel things that you normally don’t feel.

Sin that you might normally brush off might weigh a little heavier this week.

You might resonate with Jesus—feeling at least a fraction of what he felt. Your own sorrow will find company in his.

Finally, and most importantly, if you embrace this Holy Week, you will become a little more like Jesus.

Or you will at least want to.

This is the goal of the Christian life.

Have this mind among yourselves—says St. Paul—which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form he humbled himself and became obedient unto death, even death on a cross.

Perhaps more than anything, Holy Week reminds us that the Jesus we follow as Lord and King is also a wounded Savior.

It is easy to talk about being the hands and feet of Christ in a broken world.

It is harder to remember that those hands and feet still bear the marks of nails.

In the first century, as the persecution of Christians in Rome was growing increasingly intense under Nero, leaders in the Church convinced St. Peter to flee the city.

They could die, but surely their Apostle and Bishop needed to survive in order for the Church to continue.

As Peter made his way out of the city, he encountered Jesus, carrying a cross, making his way towards the city.

Quo vadis, domine? “Where are you going, Lord?”

“I am heading to Rome, Peter. To be crucified in your stead.”

An early Christian history called The Acts of St. Peter tells us that Peter got the message.

He returned to Rome, where he was crucified upside down.

Have this mind among yourselves which is yours in Christ Jesus.

There are countless examples of this—some more intense, some far less—between St. Peter and our own day.

Why?

A willingness to be the crucified hands and feet of Christ is there throughout Christian history and today because of the hope of the resurrection.

Because, through Holy Week, we know that death is not the end. That we have a Lord who has gone before us, who fought the battle we could not win, even to the very depths of hell.

And that he came back.

All of this is here in Holy Week.

So make plans to experience it.

Go to church on Maundy Thursday as Jesus shares his Last Supper with the disciples and is betrayed.

Experience Good Friday afresh, playing the part of the crowd who shouted “Crucify him.”

Embrace the quiet, dark tomb of Holy Saturday.

And then join in the Feast of the Resurrection of our Lord.

It is not convenient. It will throw a wrench in your schedule.

But Jesus is alive and ready to meet you again in new and old ways this Holy Week.

Amen.

To all those who love soccer, and to those who don’t but love someone who does.

The dedication page of Laurent Dubois’ The Language of the Game

On Leisure and Work (Josef Pieper)

One of Josef Pieper’s central claims in his 1948 Leisure: The Basis of Culture is this: we place too much value on hard work, and as a result our happiness, productivity, art, and ability to flourish as a human society is suffering.

Here are just a few nuggets from the book:

The inmost significance of the exaggerated value which is set upon hard work appears to be this: man seems to mistrust everything that is effortless; he can only enjoy, with a good conscience, what he has acquired with toil and trouble; he refuses to have anything as a gift.

In other words: our over-emphasis on work has made us less capable of receiving life as a gift.

There is more:

Of course the world of work begins to become - threatens to become - our only world, to the exclusion of all else. The demands of the working world grow ever more total, grasping ever more completely the whole of human existence.

We tend to overwork as a means of self-escape, as a way of trying to justify our existence.

His recommendation for recovering a better approach to work is actually to recover a better approach to leisure.

Leisure is “an attitude of mind and a condition of the soul that fosters a capacity to perceive the reality of the world.”

When we overwork, we perceive the universe poorly, placing our own effort at the center. Good Leisure can help correct this poor vision.

St. Joseph, March 19 (Usually)

St. Joseph is a model of quiet, often thankless work that paves the way for Jesus to be known and loved.

The Feast of St. Joseph is usually celebrated on March 19th. When specific Feasts fall on a Sunday, their observance is usually transferred to the following weekday. This is because every Sunday is a Feast of our Lord’s Resurrection—and in that sense—the celebration of Jesus’ Resurrection is not shared with any other celebration. So for this year, today (March 20) is the formal Feast of St. Joseph. Celebrate away!

George Weigel describes the history of God’s dealing with humanity as “an extraordinary story involving some utterly ordinary people.”

An adopted son of a slave with a speech impediment is used by God to accomplish the greatest saving act of the Old Testament. The King of Persia’s bartender is used by God to restore the city of Jerusalem after its destruction at the hand of Babylon. A group of ragtag fishermen and rabbinic school dropouts are used by God to establish the Christian Church, and are told by Jesus that they will spend the rest of their lives doing “greater things than these.”

And right in the middle of this extraordinary story lies Joseph of Bethlehem. An ordinarily quiet dad who works hard, forsakes his legal freedom to dismiss Mary, and instead bears the brunt of communal shame so his new wife doesn’t have to. (Not to mention that his first experience in parenting involved raising the Son of God.)

I am the proud owner of multiple pairs of socks that feature Saints from the Scriptures and Christian history. The side of each sock bears the image of the Saint, and on the bottom of each foot is a famous quote from their life and work.

As a (sometimes) quiet dad myself, I naturally own a pair of Saint Joseph socks.

And printed on the bottom of each foot is the following quote:

“ ."

- St. Joseph

Joseph has no recorded words in the Christian Scriptures. He is visited by an angel. He leads his family on several journeys: first to Bethlehem for the less-than-glamorous birth of Jesus, then to Egypt, this time as refugees. And after several quiet years in Egypt, Joseph leads his family once more to settle down in the podunk town of Nazareth. And from this point on, we know very little about how Joseph spent the rest of his days.

We see in St. Joseph a model of quiet, often thankless work that paves the way for Jesus to be known and loved.

Habit to Adopt: At some point throughout our week, we all have quiet, thankless work to do. We are washing the dishes, or filing papers, or taking out the trash. The next time you catch yourself doing this routine work, turn off the TV, take out the headphones, or otherwise limit distractions. Allow the quiet—and the noise of the work itself—to remind you to pray that God will use your otherwise menial task to somehow make Jesus known and loved.

What was before him appeared no longer a creature of corrupted will. It was corruption itself, to which will was only attached as an instrument. Ages ago it had been a person, but the ruins of personality now survived in it only as weapons at the disposal of a furious self-exiled negation.

Perelandra, C.S. Lewis, Chapter 12, during Ransom’s fight with the Unman.

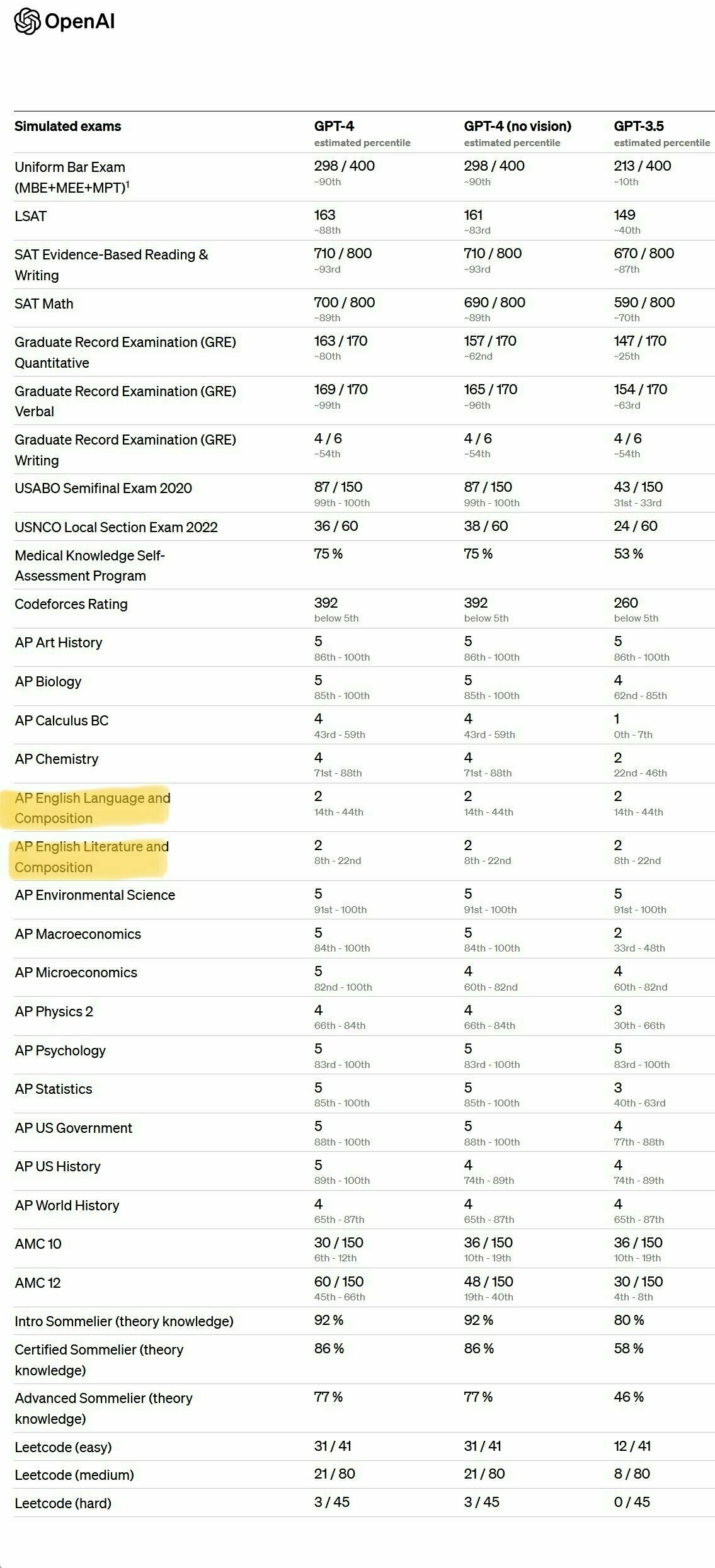

GPT-4 scores well on a variety of common academic benchmarks, but I am most intrigued—though not surprised—by where it falls comparatively short:

AP Language and Composition (Rhetoric) and AP Literature and Composition.

These are the most humane benchmarks it has encountered.