Lent

Sermon: Praying Psalm 22 in the season of Lent

A sermon from Lent 2024 on adopting Psalm 22 as a prayer for Lent.

Lent as an Exercise in Dependence

Becoming more human in an age of information

In 1948, Claude Shannon published a paper on the Theory of Information and Communication that set the stage for an understanding of Information as data - bits of sound that are capable of being transmitted in an orderly fashion across great distances.

Eventually this work led to the creation of what we call the internet and the dawning of the Information Age.

Today, we know more than we ever have, and we can share that knowledge with just about anybody anywhere at any time.

But the Information Age comes with some unintended consequences.

We used to ask our dad, or our neighbor, or a stranger how to change a tire. Now we ask a machine.

If we had a story to tell or an opinion to share, we used to do this around a table or while working side-by-side or at the weekly market. Now we read—or at least start to read—posts and articles written by strangers who we will never have the chance to personally engage.

And all of this is heralded as good news.

Our age is built around the premise that information will save you.

Do you have an unusual or embarrassing rash developing? Need to know what sporty business chic attire means for your nephew’s wedding?

Ask Google.

Life in the Information Age is convenient. We are more informed now than we ever have been, but there is a catch.

Vivek Murthy is the current surgeon general of the United States. In 2017, towards the end of his previous term, he wrote this:

During my years spent caring for patients, the most common pathology I saw was not heart disease or diabetes. It was loneliness.

Andy Crouch once said that the Information Age is a great place to gain information and power, but is not a great place to be a human person.

This is, in one sense, a progression of history: the obsession with information over wisdom in the 20th century led to a modern, lonely society. But it is actually an ancient problem—perhaps the most ancient of problems.

In Genesis we are told that Adam and Eve went from walking and talking with God in the cool of the day to being banished from his presence. This disconnect affected their relationship with God, to be sure, but also their relationship with one another. After leaving the Garden, humanity began the long journey of being alone together.

All of this, because Adam and Eve wanted a shortcut to wisdom.

Wisdom was meant to be slowly gleaned through a relationship with God, not grasped in an instant.

But when our First Parents took and ate of the fruit of that tree, it represented an attempt to shortcut this process. It was a desire for information instead of relationship.

Satan said to Eve, ‘For God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil’

After they ate, notice their first reaction:

They covered their most intimate parts from each other, and then they hid from God.

The human pursuit of information and power over relationship began in the Garden of Eden. And it has continued—with destructive results—ever since.

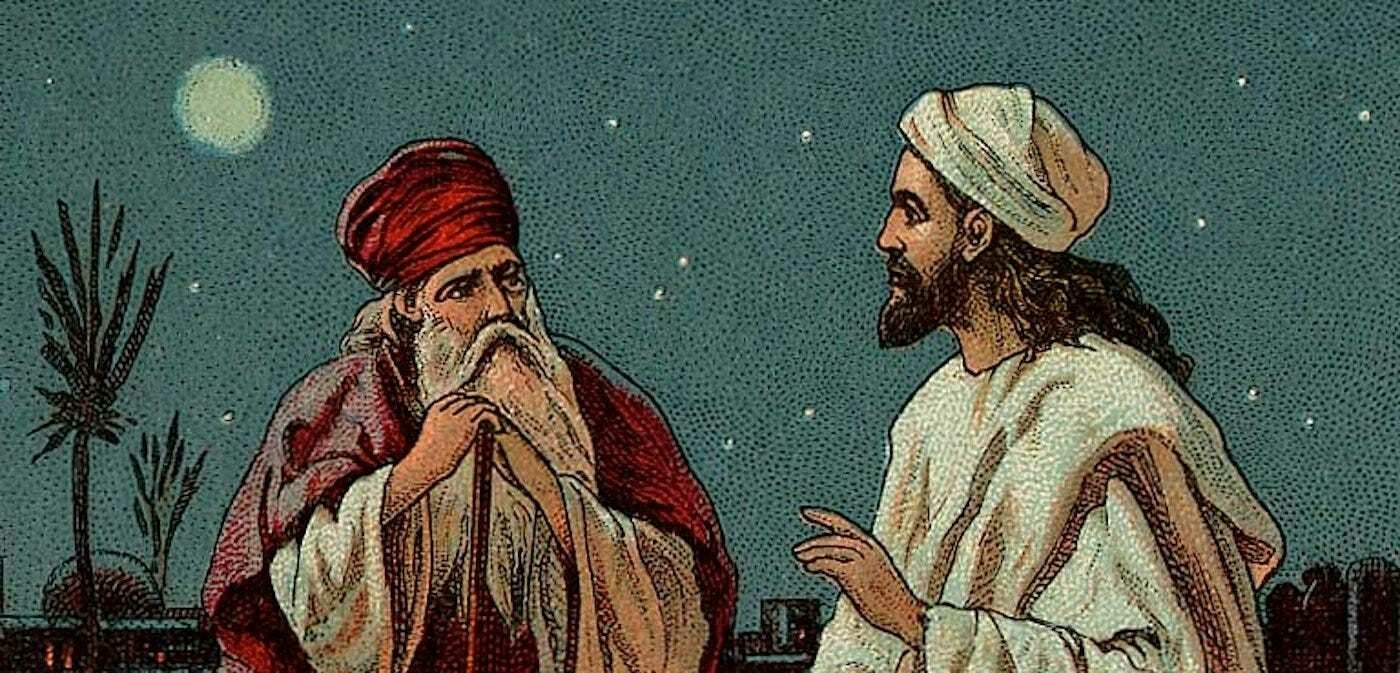

Fast forward from Genesis 3 to John 3—to a late night conversation between Nicodemus and Jesus. A different context, a mostly different cast of characters, but the same old story.

Nicodemus is a fascinating character throughout the Gospel of John. He is a Pharisee—a member of the Jewish sect that was convinced that God would send his kingdom once his people got their act together and started following the Law. The whole Law.

And in order for that to happen, God’s people needed to know how to read the Law, and properly interpret the Law, and properly follow the proper interpretation of the Law.

As you can imagine, to pull this off would require a lot of teachers teaching a lot of students a lot of information. There were few communities better at transmitting information in the ancient world than the Pharisees.

We don’t know if Nicodemus was sent by the Pharisees or if he was just curious, but we do know this: he snuck out in the middle of the night to ask Jesus a question.

Nicodemus was seeking information.

Rabbi, we know that you are a teacher come from God; for no one can do these signs that you do, unless God is with him.

I would like for you to teach me something, Jesus. Do you have any nuggets of wisdom for me? Any new teaching that I can add to my repertoire? Something I can share with my friends at a dinner party to sound like an intellectual?

Sure, said Jesus, here you go: If you want to live forever, you need to experience birth again.

It is a jarring response, isn’t it?

But Jesus isn’t finished. When Nicodemus justifiably expresses confusion over this saying, Jesus rebukes him:

Are you a teacher of Israel, and yet you do not understand this?

In other words: how is it that you spend your days reading and meditating on the Scriptures, and yet still think that the problem with humanity is a lack of information?

Nicodemus came to Jesus seeking new information; what he needed was new birth.

Birth is one of several running images throughout the Scriptures. There is something about birth that captures the core of where a redeemed person stands in relation to God.

In other words, there are several things that are true about physical birth that ring even more deeply true about spiritual birth.

To be born is to utterly depend upon another. This is obvious on one level: an infant cannot feed themselves or move on their own. Parents of newborns can attest that they can hardly even sleep without being cared for by someone other than themselves.

This is true of many creatures, but it is most true of humans.

We are born long before we are capable of sustaining ourselves. Other mammals are born with far more developed brains than we are. (Parents around the world can attest to this…)

A human fetus would need to remain in the womb for 18 to 21 months in order to match the neurological and cognitive development stage of a newborn chimpanzee.

Simply put: Human Beings were created to be relationally dependent.

We grow out of some of this dependence in some truly important ways, but by and large humans only flourish when we share some level of dependence on another: a neighbor, a roommate, a friend, a spouse, a child, a parent, and ultimately, God.

Embracing this dependence on God is the crucial first step on the journey that is the Christian life.

Nicodemus’ last words to Jesus in this encounter were simply, “How can this be?”

We don’t know if Nicodemus was changed that night. But John does leave us some clues. Nicodemus appears two more times in his Gospel.

The next Nicodemus sighting comes when Pharisees are arguing with the Temple Police about arresting Jesus. Nicodemus speaks up, suggesting that they not rush to judgment on Jesus and his teaching.

John leaves us with the impression that perhaps Nicodemus has been intrigued by what Jesus said to him.

But the final sighting of Nicodemus in the Gospel of John is perhaps the most convincing. We encounter it each year on Good Friday—at the very end of Holy Week.

After Jesus is crucified, John tells us that Nicodemus

who had at first come to Jesus by night, went to Jesus’ tomb, bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes, weighing about a hundred pounds. He took the body of Jesus and wrapped it with the spices in linen cloths.

The man to whom Jesus said You must be born again was now wrapping our Lord in burial clothes adorned with spices.

I think it is safe to say that Nicodemus had experienced new birth.

The problem with humanity is not a lack of information. You and I are not one New York Times opinion piece away from a changed life.

Our first, second, and final step towards eternal life is to recognize, and then embrace, and then eventually enjoy our dependence on God.

Perhaps more so that any other Liturgical season, Lent can help move us along the path towards increased dependence.

The failures we experience throughout Lent are part of the gift of Lent.

When you find your fasting difficult to maintain, or when you drop a practice that you meant to maintain throughout the season, allow these shortcomings to remind you of your utter dependence on God.

Lent: Effort and Grace in Action

One of my favorite bits of dialogue in Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring presents us with an age-old debate about spiritual disciplines in general, and the Christian season of Lent in particular.

Before embarking on their Journey to Mordor, Elrond—the Lord of Rivendale—shares a final message with the Company that is to join Frodo on his quest.

Frodo himself is bound to complete the journey, while the members of the Company are “free companions” that may “come back, or turn aside into other paths, as chance allows.” Gimli, the renowned Dwarf warrior, gives a response that begins the dialogue in question.

‘Faithless is he that says farewell when the road darkens,’ said Gimli.

‘Maybe,’ said Elrond, ‘but let him not vow to walk in the dark, who has not seen the nightfall.’

‘Yet sworn word may strengthen quaking heart,’ said Gimli.

‘Or break it,’ said Elrond.

Gimli argues that a vow made on the front end of a journey may serve as a sustaining force for when difficulty is faced. Elrond counters that, at times, the weight of such a vow might actually break one’s will along the way. Both positions are worthy of considering further, but what light can this conversation shed on the ancient Christian practice of Lent?

The Church Calendar has historically served as a way to center our lives around the life of Christ, and the season of Lent serves (1) as an opportunity to re-live Jesus’ forty days of fasting in the wilderness and (2) as a period of preparation for our celebration of the Crucifixion and Resurrection. It has traditionally been celebrated as a season for fasting, the adoption of a new spiritual practice, and giving of time and money to the poor. These practices are not particular to Lent, but are in fact some of the most central practices of the Christian faith, commanded repeatedly throughout the New Testament (see Matthew 6:1-18). In this sense, Lent is a season that simply asks Christians to act as Christians.

So how then should we approach Lent? With Gimli’s determination and rigidity, or with Elrond’s patience and grace?

The Church’s answer to this questions, as is so often the case, is “yes” to both.

Be like Gimli as you fight against sin in your own life and injustice in the world. Use this period of 40 days to re-center your spiritual life. Don’t allow our various cultural calendars dictate your devotion to Christ. Put forth effort to “work out your salvation with fear and trembling” (Philippians 2:12). On Ash Wednesday, after all, the Church is called to “the observance of a Holy Lent.”

But also remember that we are often more like the first Adam, who failed his temptation in the garden, than we are like the second Adam, who triumphed over temptation in the wilderness.

Be like Elrond as you let your failure during this season serve as another reminder of your need for a savior. Don’t let your adoption of new disciplines “puff up” your ego, but instead recognize them for what they are: gifts from God given to a sinner who does not deserve them.

May this Lenten season be for us one more way “that we may remember that it is only by God’s gracious gift that we are given everlasting life.” (BCP, 265)